Introduction

Wrenches are one of the most common tools that we use in the home shop and in any type of mechanical maintenance. They come in all sorts of flavors, sizes, and shapes. In this post we will review the most common types of wrenches, how they are used, and the correct way the end user should put them to work. We won’t cover every wrench out there, but hopefully this will give you a good platform to build upon. I know this is a very basic topic but remember that the beginning of any craft is a good foundation. Our basic skills allow us to place those initial building blocks from which we place those more complex structural pieces.

Combination And Adjustable Wrenches

Combination and adjustable wrenches are the most common wrench used in the trades. The basic styles of these wrenches include the open-end, box-end, and combination wrench. The open end has that recognizable C-shaped head sized to the hex shaped fastener you may be working (7/16, 5/8, 17mm, etc.). Typically, these wrenches have the open-ended feature on both ends of the tool with apposing sizes that are close in width such as 11/16 on one end and 13/16 on the other. These are mostly utilized in general loosening or tightening of a bolt and are not meant for higher tightening torques. Being that the only real contact surfaces are the 2 that contact either side of the mouth the excessive force can cause deformation of the fastener head or spreading of the mouth of tool.

The box-end wrench has a totally enclosed working end and routinely have a 6- or 12-point profile. The 6-point profile is the best option for optimal contact with the bolt head and for heavier tightening or that stubborn bolt that just won’t break loose. The downside is that 6-point wrench can make it difficult to utilize in locations where space is limited. The 12-point, on the other hand, allows the user to “attach” to the bolt head in finer increments enabling a better range of motion. Like it’s sister, the open-end, the box-end wrench comes in a multitude of imperial and metric sizes and have opposing ends that are close in width.

The combination wrench is the best of both worlds and usually the favorite of most mechanics. It sports an open-end head on one end and box-end on the other. The design standard for these is the same head size on both ends.

The adjustable wrench is the multi-tool of wrenches. It’s an open-end design with a fixed jaw and movable jaw. By turning the worm screw on the head of the tool the moveable jaw will open or close to adjust to the size of the fastener head. These can be bought in many different lengths, but the most common are 6”, 8” and 10”.

Most of these are made from an alloy steel, drop forged, and plated for corrosion resistance. Drop forging is when the material is placed in a die and a hammer is struck against the material thus forming it to the shape of the die. There are 2 types open-die and closed-die drop forging. When using and adjustable, the direction of movement should be in the direction of the moveable jaw thus putting the bulk of the force on the fixed jaw. This really hold true for open-end wrenches also. The direction of movement should be towards the bottom jaw of the head. You learn that lesson quickly when and old mechanic yells as you for using the tool the wrong way. But to be honest, I don’t know a mechanic that hasn’t used them in both directions. As a best practice, when loosening or tightening a bolt you should try to be in a position to pull the wrench towards you for the best control. Care should always be taken when using an open-end and adjustable wrench as it’s easy to slip and cause the infamous “knuckle buster”. I have many hand scars to validate both of those last bits of advice.

Last, but certainly not least, always use the correct size. If you are unsure there are a couple things to look for. Standard bolts will typically have 0, 3, or 6 indicating marks on the head. Metric will likely have numeric marking such as 8.8 or 10.9 to represent the grade. While this is a quick way to distinguish metric from standard, depending on the quality of the bolt, it may not always hold true. The best method is to place the estimated size wrench on the head of the bolt and move it slightly back and forth. There should be very little movement from contact point to contact point. It should be a good solid fit. If excessive, then it’s not the correct size or incorrect unit denomination (metric vs imperial). As you progress in this type of work you get to a point where you can look at a bolt head and know the size wrench needed for the job. These little tips will not only keep your hands less bloody, but they will also keep your tools and fasteners in better shape.

Socket Wrenches And Breaker Bars

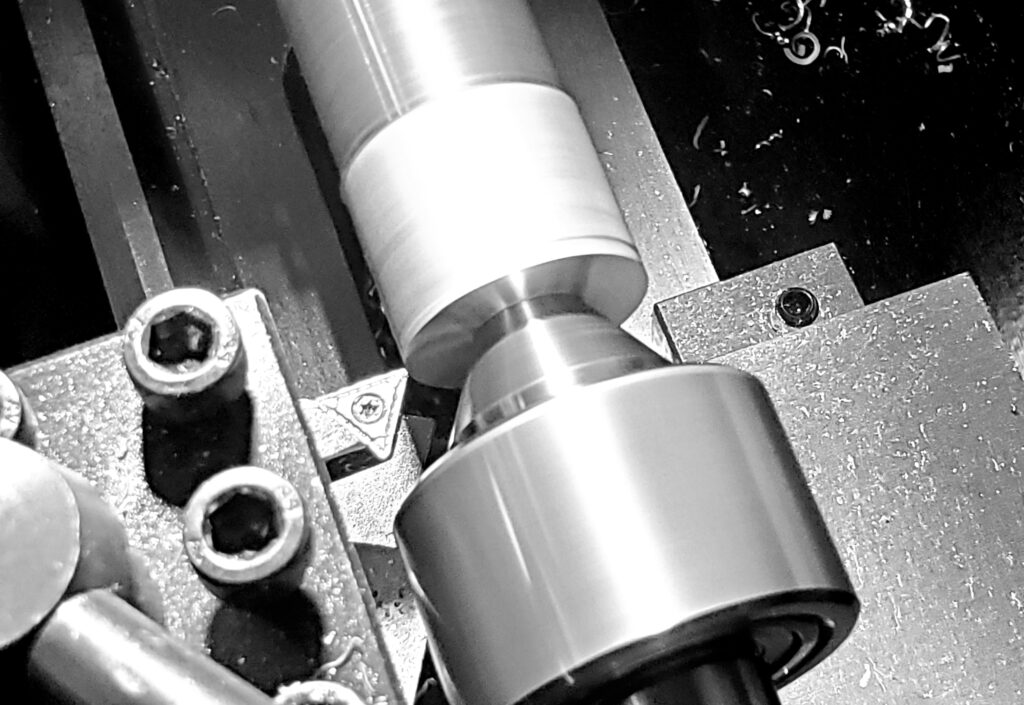

Socket and the previously mentioned open/box-end wrenches are different yet cut from the same cloth. The benefit of the socket wrench is its ability to ratchet in both directions preventing the user from having to remove the tool from the head of the bolt. The wrench by itself isn’t of any use without the addition of the socket. Sockets are designed to fit various size hex heads and are commonly found in 6 and 12-point profiles. The end opposite the profile has a square drive hole made into the socket. This female feature is where the socket couples to the male drive of the wrench. Standard drive sizes are ¼”, 3/8”, ½”, and larger. Obviously the larger the drive size the larger the socket, the less space the too will fit into and the more torque the tool can withstand.

The ratcheting action of the unit is also variable from model to model. From course (20 to 40 tooth) to low (72 to 160 tooth) the number of teeth will dictate how far the drive of the head needs to rotate in order to “ratchet” into the next tooth. Ultimately this dictates the degree of swing to advance the ratchet and force to the next driving surface. Many say that the more teeth a ratchet has the weaker and more susceptible to damage when excessive forces are applied. While that may be true in some instances, I believe a lot of that depends on the quality of the tool.

The breaker bar is the juiced up big brother to the socket wrench. This tool is designed to break extremely tight bolts loose and tighten loose bolts extremely tight. The head design contains no ratcheting gears. Instead, the end sports a forked yolk that allows the drive portion to swivel 180 degrees perpendicular to the handle. These too come in the standard drive sizes and the handles are usually longer than it’s ratchet counterpart.

There are a ridiculous number of accessories like extensions, universal joints, adapters, etc. that can be used to adapt the tool to the job and conditions. Obviously, we won’t go into all of those in this post. Safety and use are pretty much identical to that of the common wrench. Pull don’t push and try to utilize two hands, meaning one hand on the handle and the other on the head to stabilize and square the tool. And although tempting, never use a “cheater” bar on the handle. For those who may not be familiar with the infamous cheater bar it’s a piece of pipe to extend the length of the handle to gain a mechanical advantage.

Pipe And Strap Wrenches

As indicated by the name the pipe wrench, or sometimes called the monkey wrench, is intended for use in metal pipe fitting. The pipe wrench, also referred to as a monkey wrench, is much like an adjustable wrench with the added advantage of a toothed profile on the fixed and moveable jaws. This feature allows the tool to bite into the round thing being rotated like a pipe. The naming of the individual parts differs from the adjustable wrench. The moveable jaw is referred to as the hook jaw, the fixed jaw is the keel jaw, and the ring used to adjust the size of the opening is called the knurl. Sizes vary and are usually directly proportional to the intended pipe to fitted. In other words, the bigger the pipe the bigger wrench. They are usually constructed out of iron or aluminum. Both types are more that suitable for the average home handyman, but of course the iron construction is designed for heaver torque loads.

Like the pipe wrench, the strap wrench is used to get a grip on round things. They can be used for everything from pipes to oil filters, to removing lids off jars. The gripping material can be that of nylon, metal, chain, and even rubber. Straps constructed of chain or metal give the best bite into the material while softer straps are the best for materials in which you don’t want to damage the surface. The are usually designated by the length of the strap and typically have an integrated handle. The fancy designs can even incorporate a ratcheting mechanism to firmly cinch the strap around the work.

When using a pipe wrench, you want to adjust the opening to a point where it’s not too tight or loose. Needs to be tight enough to get a good bite on the work but not so loose to where it skips off the surface. Adjusted right, the pipe fits fully in the throat of the jaws and grabs into the material securely. These only work correctly when the force and direction of rotation is in that of the bottom, keel jaw. Strap wrenches typically have a arrow that indicates the direction of rotation. Depending on whether you are loosening or tightening, loop the strap around the work in the orientation for the correct rotation. Tighten the strap down, get a good grip on the handle, and apply even pressure against the handle in the direction of rotation. Poof……you just graduated to strap wrench guru!

Hex Key Wrenches

Hex key, or allen wrenches, completely different from all the tools previously mentioned, but they still fall into the wrench family. The most common is the L-shaped design with a hex profile on both ends sized to fit a socket head screw. Some additional styles include T-handle, screwdriver handle, ball-end, torx end, and sockets with hex key ends used with socket wrenches. The advantage of the fore mentioned ball-end is that the tool can engage the head of a screw at various angles versus the need to be perpendicular. The disadvantage is that the ball-end is only intended for light loosening and tightening. Excessive force can cause the end to sheer off thus turning your fancy ball-end into a flat-end.

The key to use of these tools is to use the right size for the socket head screw you’re working with. Metric for metric screws and standard for standard. Using the incorrect size will undoubtedly result in damage to the wrench and socket of the bolt. Too much damage to the screw and you will either need to walk away and pretend like that screw doesn’t exist or use another extraction method/tool to get it out. Most of the time I just pretend like someone else made the mistake 😁. A good thing about the hex key is that if the ends get rounded off you can hit them on a bench grinder to flatten them back out.

Conclusion

We’ve covered the basics of wrenches and the use of each type. With enough time and stronger typing fingers we could dive into the rabbit hole on each one and discover far more that what has been outlines, but that’s not the intent. I hope this has been a good basics guide to a family of tools that have many uses in any shop and tool bag. The key is always using the right type and size tool for the job. When we use the tool as designed, then increase the longevity of the tool, we are more efficient, safer, and take step one step closer to perfecting the craft of good workmanship.